Still, visiting the doctor is too expensive in all cases. Yes, healthcare is expensive, but it is important to understand why – and whether it is affecting the quality of care. Then, we can make an educated determination as to whether it is “too” expensive for what the American people are receiving back. The answer is a more confusing “it depends.”

In our first article, we discussed how U.S. healthcare consumption expenditure per capita has never

grown more slowly than it has during the current decade, in which the growth rate has been nearly in-line with U.S. GDP growth per capita, according to CMS. U.S. healthcare has been around 17.8% of GDP for quite a while, not really growing, not shrinking.

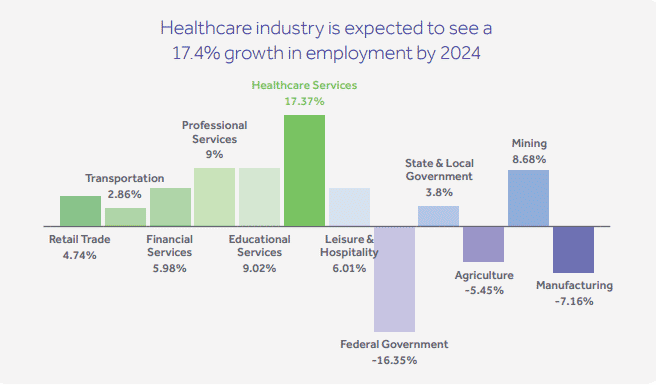

The cumulative growth in overall healthcare prices from 2005 to 2018 was 29 percent, but hospital

prices increased 36 percent while prices paid for physician and clinical services grew 18 percent.

This seems like a small difference, prices went up everywhere. But on an annual net basis one group, the hospital group driving price increases in healthcare at 2x the rate of another group, the physician group is a very big deal.

One reason is that hospital health system consolidation has increased in recent years, in parallel with hospital price increases. Correlation between this activity and prices has been established in certain states, like California.16 With market control, health systems can demand higher prices. Insurers are

paying out more as a result and thus passing costs to patients. In 2000, private insurers in the U.S. paid about 10% more for health care services than public insurers did; by 2017, they are estimated to have paid 50% more.

And, that extra hospital revenue is partly going into marketing. Have you too noticed all of the highway

billboards advertising hospitals? Large health systems are creating brands, and it is working. People

pay for brand-names, for fashion, drugs, and health systems alike. In medical settings – as is the case

in most industries – consumers equate price with quality.18 We are not saying that the quality of care in smaller practices is poorer than it is in large hospitals. In fact, the opposite may be true.

And, most importantly, we are also saying that hospital cost implies neither better nor worse quality care. The media focuses on how increasing prices is not equating to better quality. That is a very dif�ficult statement to support. In many fields such as cancer we have seen incredible increases in quality and outcomes. One thing is certain, pointing to life expectancy on its own, or a basket of pre-selected medical outcomes is not a conclusive argument.

Also, prices remain high albeit increasingly transparent and subject to therefore more competition. But not everyone is paying directly for them (more to come on that in the next section). If you have insurance, you only pay out-of-pocket price and not the full price. There is a reason why the President, in his 2020 State of the Union Address, said 180 million people do not want to let go of their private insurance. It shields them from the full price that we pay for the often great care we receive.

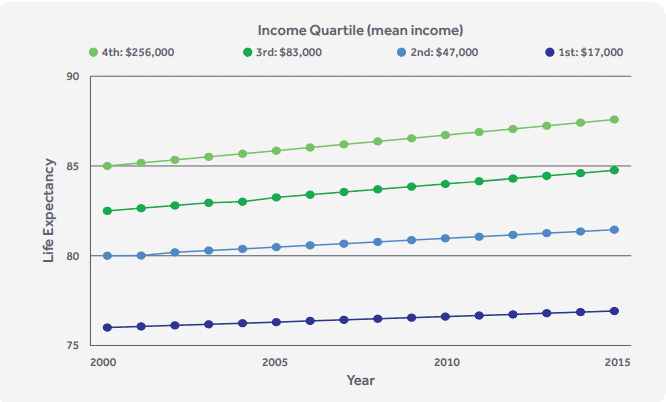

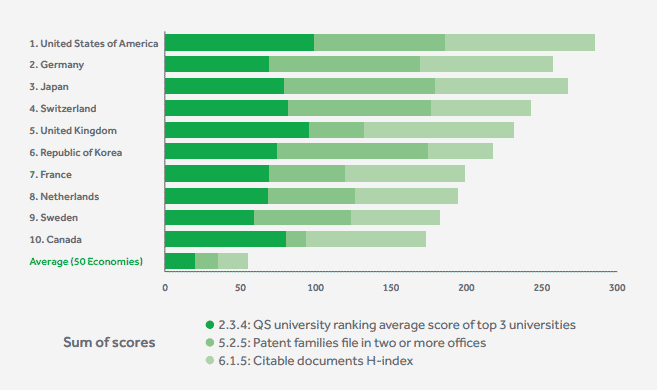

How does America compare to other countries? We as individuals are actually not paying much as

individuals. According to the World Health Organization, the United States had an 11% rate of out-of�pocket spending as a percentage of total national health spending and a 2.6% rate as a percentage of household consumption in 2016.21 Compared to other nations, as seen in a sample of the list below, we are not paying that much.